The announcement was met with applause. At Davos 2026, Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw unveiled India’s ambitious plan: 12 companies, 22 languages, one grand vision – building indigenous Large Language Models under the IndiaAI Mission. The budget? A staggering ₹10,370 crore (roughly $1.2 billion).

I’ve watched this movie before. And I know how it ends.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that nobody in the policy corridors seems willing to say out loud: building foundational LLMs is quite possibly the worst investment a developing nation can make in 2026. Not because AI isn’t important – it absolutely is – but because the economics of frontier LLMs are, to put it bluntly, catastrophic.

OpenAI, the company that started this whole revolution, is projected to lose $9 billion in 2025 on revenues of $16.7 billion. Anthropic? They’re burning through $5.2 billion this year alone. These aren’t startups figuring things out. These are the world’s most well-funded AI labs, backed by the deepest pockets in tech, and they’re hemorrhaging cash at rates that would make any CFO faint.

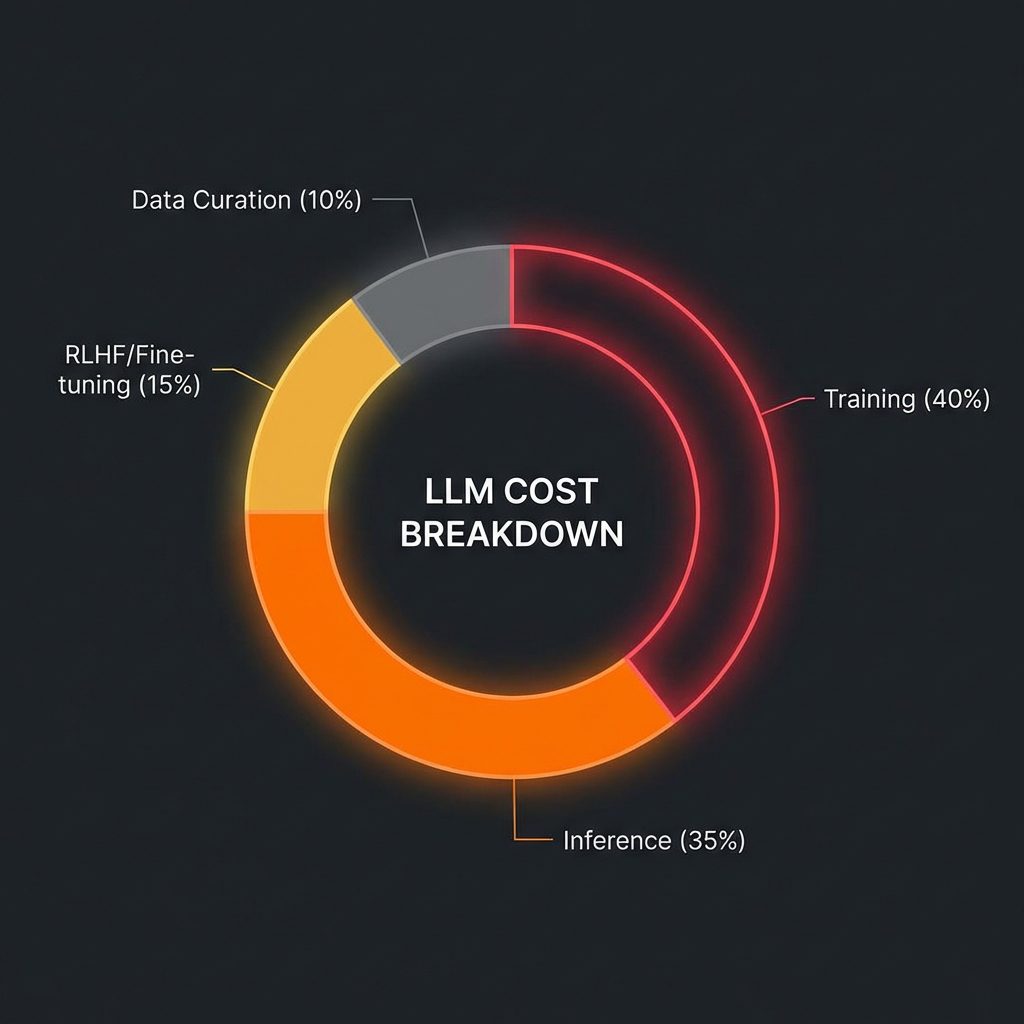

Where the money goes: The brutal reality of LLM economics.

So why exactly does India think it can succeed where Silicon Valley’s finest are failing?

The Hallucination Tax: What Nobody’s Talking About

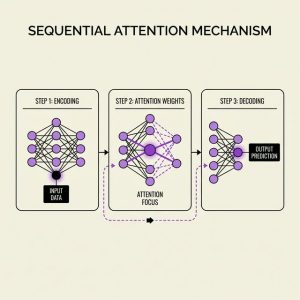

The economics of frontier AI – cash transforming into increasingly expensive neural pathways.

Let’s get technical for a moment. The fundamental problem with LLMs isn’t just the compute cost – though that’s a significant factor. It’s what I call the “hallucination tax.”

Every LLM, regardless of who builds it, generates confident nonsense a certain percentage of the time. For consumer chatbots, this is annoying. For military applications, healthcare diagnostics, or financial systems – the domains where India actually needs AI – it’s potentially catastrophic.

And here’s the kicker: reducing hallucinations requires exponentially more compute.

Think of it like this. Going from 10% hallucination rate to 5% might require doubling your training compute. Going from 5% to 2.5%? Double it again. This is why OpenAI’s inference costs are spiraling and why companies like Anthropic are discovering their server costs are 23% higher than projected. The physics of LLMs create diminishing returns that get worse – not better – as you scale.

For a country with limited compute resources and competing priorities, this is a trap. We’d be building expensive models that we can’t afford to run, to solve problems that require precision we can’t achieve.

The Constraint-Based Alternative: Where Physics Beats Probability

Precision engineering AI – where physics constraints replace probabilistic hallucinations.

But here’s what excites me. While everyone’s obsessed with chatbots, a quieter revolution is happening in computational AI – and it’s one where India could genuinely lead.

In June 2024, a Dubai-based company called LEAP 71 hot-fire tested a rocket engine that was designed entirely by AI in less than two weeks. The Noyron TKL-5 engine generated 5 kN of thrust and produced 20,000 horsepower. The design-to-manufacturing timeline that normally takes years? Fourteen days.

This wasn’t an LLM hallucinating rocket designs. This was a physics-constrained computational model that understood the laws of thermodynamics, material science, and fluid dynamics. No hallucinations possible – the physics either works or it doesn’t.

NASA is doing something similar. Their Jet Propulsion Laboratory recently used AI to plan paths for the Perseverance rover on Mars, analyzing 28 years of mission data to generate safe navigation routes. This isn’t GPT writing poetry about Mars. This is constraint-based AI solving real engineering problems with zero margin for error.

This is the AI India should be building.

PARAM’s Untapped Potential

Here’s what frustrates me about the current strategy. India already has world-class high-performance computing infrastructure. PARAM Siddhi-AI delivers 210 AI petaflops. The National Supercomputing Mission has deployed 37 supercomputers with 39 PetaFlops of capacity. We’re building a 30-petaflop facility in Bengaluru specifically for research in AI, quantum computing, and climate modeling.

These machines aren’t toys. They’re specifically designed for computational heavy-lifting – weather prediction, monsoon modeling, materials science, pharmaceutical research.

So what are we doing with them? Planning to train yet another chatbot.

The irony is painful. We have supercomputers purpose-built for computational physics, and we’re trying to make them do what they were never designed to do – compete with massive language models that require different optimization profiles entirely.

What if we used PARAM for what it’s actually good at?

Domain-specific AI that solves India’s actual problems:

- Agricultural yield optimization using satellite data and climate models

- Drug discovery acceleration for tropical diseases

- Monsoon prediction systems with higher accuracy

- Defense systems that require deterministic outputs, not probabilistic guesses

These are constraint-based problems where the answer is either right or wrong. No hallucinations. No expensive RLHF training. No 30x energy penalty for chain-of-thought reasoning.

The Open-Source Goldmine We’re Ignoring

And here’s the part that makes the least sense. Even if India wants conversational AI capabilities – which we absolutely need for citizen services and accessibility – we don’t need to build it from scratch.

DeepSeek-R1, the Chinese model that shook the AI world, isn’t just open-source. It’s been distilled into Llama and Qwen variants that run on modest hardware. The DeepSeek-R1 Distilled Llama 70B performs comparably to GPT-4o on reasoning benchmarks. For a fraction of the cost.

Enterprise-grade open-source models like Qwen 2.5, Llama 3.2, and the distilled DeepSeek variants are available right now. They can be fine-tuned on domain-specific data. They can be run on-premises for data privacy. They can be customized for Indian languages without building from the ground up.

The Chinese AI labs aren’t building everything from scratch either – they’re iterating on foundations and optimizing for specific use cases. That’s not weakness. That’s intelligence.

The Chip Reality Check: Bandwidth is the New Nanometer

Now let’s talk about India’s semiconductor strategy, because it directly impacts this discussion.

Tata Electronics is bringing online a 28nm fab in Dholera by late 2025. That’s genuinely exciting. But 28nm chips aren’t designed for training trillion-parameter models. They’re designed for exactly the kind of edge inference and specialized compute that constraint-based AI requires.

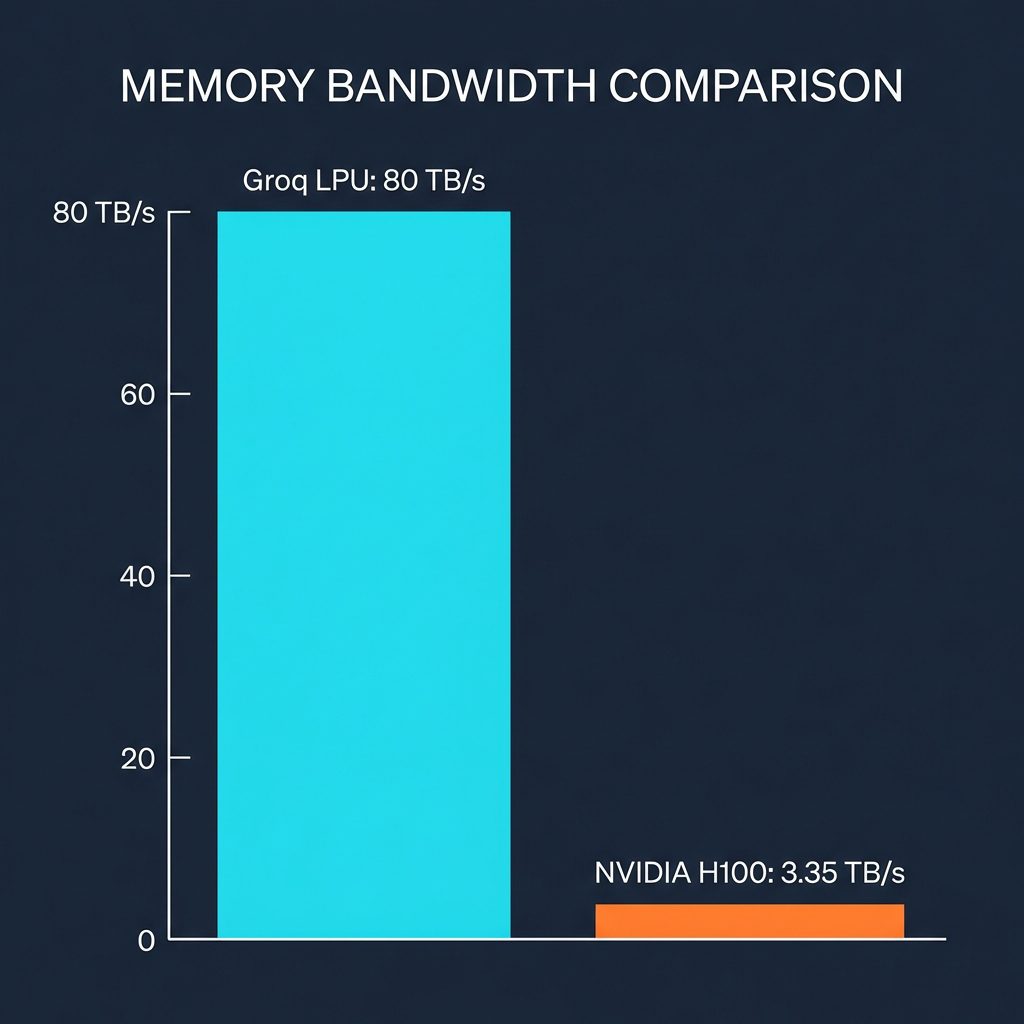

Here is the technical reality: LLM inference is memory-bound, not compute-bound.

In the “prefill” phase (processing your prompt), GPUs are efficient. But in the “decode” phase (generating the answer token-by-token), the bottleneck shifts. The processor spends most of its time waiting for data to travel from memory (HBM) to the compute units. This is the Arithmetic Intensity problem. If your ops:byte ratio is low, your expensive H100s are sitting idle 60% of the time.

This is why companies like Groq represent a paradigm shift. Their LPU (Language Processing Unit) architecture ditches the GPU model entirely. Instead of massive HBM bandwidth (which is still slow relative to on-chip speeds), Groq puts memory directly on the chip. We’re talking about 80 TB/s of memory bandwidth compared to the 3-5 TB/s you get on a flagship NVIDIA GPU.

The Memory Wall: Why on-chip bandwidth matters more than raw FLOPs for inference.

Why does this matter for India? Because Groq proved you don’t need the absolute smallest nanometer node to win at inference. You need a better architecture. You need to solve the memory wall.

India’s 28nm chips, if designed with a focus on high-bandwidth on-chip memory (SRAM) and specialized dataflow architectures, could run fine-tuned physics models or distilled LLMs faster than a generic 5nm GPU. We shouldn’t be trying to build H100 clones. We should be building inference engines that solve the memory bottleneck.

The Strategic Pivot: IBM & The Hybrid Model

While we chase the “indigenous LLM” dream, real strategic moves are happening quietly. IBM has partnered with L&T Semiconductor Technologies to design advanced processors specifically for edge devices and hybrid cloud systems. They’re also integrating their watsonx platform with India’s Airawat supercomputer to boost R&D.

This is the model we should replicate. IBM isn’t just dumping chips. They’re building an R&D ecosystem that leverages India’s design talent (which is world-class) while acknowledging that we don’t need to own every nanometer of the fabrication process immediately. We can design the brains here (IP), fabricate the mature nodes here (28nm at Tata), and partner for the bleeding edge.

The Sovereign AI Myth

I understand the appeal of “sovereign AI.” In an era of geopolitical tensions and tech decoupling, having indigenous capabilities feels essential. And for certain applications – defense, critical infrastructure, strategic communications – it genuinely is.

But sovereignty doesn’t require reinventing the wheel. China uses American mobile phones. America uses Taiwanese chips. The world’s technology stack is interconnected whether we like it or not.

True AI sovereignty means:

Controlling your data and knowing where it’s processed

Having engineers who understand and can modify the systems they deploy

Building domain expertise in applications that matter to your economy

Creating value chains where you have differentiated capabilities

It doesn’t mean spending $1.2 billion to build a worse version of something that’s freely available.

What India Should Actually Do

Let me be specific about where I think the investment should go:

1. Constraint-Based Computational AI

Use PARAM and our HPC infrastructure for what they’re designed for. Build physics-informed neural networks for engineering applications. Create domain-specific models for agriculture, healthcare, and defense where accuracy is non-negotiable.

2. Fine-Tuning and Distillation Infrastructure

Instead of training from scratch, invest in the tooling and expertise to take open-source models and optimize them for Indian languages, legal frameworks, and domain applications. The Llama Factory ecosystem makes this accessible.

3. Inference Optimization

Focus semiconductor efforts on inference chips that can run optimized models efficiently. Partner with companies like Cerebras for training if needed, but own the deployment infrastructure.

4. Applied AI Centers of Excellence

Create specialized labs for specific domains – agricultural AI, judicial AI, healthcare AI – where the problems are well-defined and the constraints are known. This is where India’s STEM talent can actually shine.

5. Edge AI for Last-Mile Delivery

Build the systems that work on low-bandwidth, unreliable networks for India’s rural population. This requires engineering innovation, not another chatbot.

The Bottom Line

India doesn’t need to be the country that builds the next GPT. That race is already being run by companies spending more on compute than our entire IT ministry budget.

What India needs is to be the country that deploys AI effectively – that takes the revolution happening globally and applies it to our specific challenges with our specific constraints. That’s not a lesser goal. That’s potentially a more valuable one.

The ₹10,370 crore being allocated to building LLMs from scratch will almost certainly produce models that are slower, less capable, and more expensive than what’s already available open-source. And meanwhile, the real opportunities – computational AI, constraint-based systems, domain-specific applications – will go unfunded.

We’re at a crossroads. We can chase the frontier in a race where we’re perpetually three years behind. Or we can define a new frontier – one where India’s engineering talent, computing infrastructure, and real-world problems create genuine value.

The choice seems obvious to me. I’m just not sure the people making the decisions are seeing it.

FAQ

Why can’t India just train a smaller, more efficient LLM?

Smaller LLMs exist (like Llama 3.2-1B or Qwen-0.5B), but they’re significantly less capable than frontier models. The real cost isn’t in training – it’s in the data curation, RLHF fine-tuning, and continuous iteration that makes models actually useful. Open-source alternatives already do this work.

Isn’t having indigenous AI important for defense applications?

Absolutely. But defense AI typically requires deterministic, constraint-based systems – not probabilistic language models. A missile guidance system that “hallucinates” is worse than useless. India should invest in the engineering AI that defense actually needs.

What about the 22 Indian languages that need support?

This is a valid concern, and fine-tuning existing models for Indic languages is absolutely necessary. But fine-tuning requires a fraction of the resources compared to building from scratch. Projects like IndicBERT and models from Sarvam AI show this path is already viable.